LATE in 2014 Keith Stevens, DFM, a long-time resident of the Village Glen at Rosebud, was informed that the President of the Republic of France had awarded him the highest level of chevalier (or knight) of the French Legion of Honour.

The award is recognition for “..risking your life for the liberation of our country 70 years ago.” This latest honour adds to those previously received: the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM), which was presented by the King at Buckingham Palace, and some 20 others from UK, French, Polish, and Australian governments.

Created in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, Keith’s Legion of Honour is awarded because of the role he and his crew played on D-Day when they bombed and disabled the concrete gun emplacements on the French coast, making it possible for the Allied Forces to invade Normandy and ultimately defeat the German occupiers.

Keith Stevens’ story could have been torn from the pages of a “Boys Own Annual.” He joined the RAAF in 1940, trained as a wireless operator/rear gunner, and subsequently flew 62 operations in a Lancaster with Bomber Command before being shot down over Occupied France. There he worked for three months with the French Resistance movement before escaping back to England.

It is difficult to imagine what it was like being part of the crew of a Lancaster. “Ops” were always at night and lasted up to ten hours; it was freezing cold, oxygen masks were required, and there were inevitable problems with navigation, engines and equipment. They were shot at by enemy fighters, “coned” by searchlights, and hit by flak. Keith’s aircraft was disabled many times and he experienced some amazing survivals. At times up to 1000 planes were involved in an operation and the casualties were huge. Of every 100 men who flew with Bomber Command, 56 were killed;this second figure would have been about 90 for the early members of Bomber Command. Others became prisoners of war and/or suffered serious injuries.

A “tour” of 30 operations was considered sufficient for crew members and most were then found jobs as instructors or ground crew. Only four percent completed two tours. Very few would have flown as many ops as Keith who was into his third tour.

Several years ago, at the insistence of a fellow resident of the Village Glen, Keith recorded his experiences in a book titled “Flak…Fighters and Fliers – An Aussie with the RAF.” Because some of his first-hand accounts are so graphic it seemed best to quote directly from his autobiography on occasions.

This is Keith’s story.

***

Early Days

Keith Stevens was born at Hampton Park on 21 February, 1919. His father, a builder, had been severely gassed on the Somme in World War One, and was advised to move to the country. Accordingly, Keith’s parents purchased 12 acres in Pound Road where they grew produce for the Dandenong market.

Keith and his older brother used to ride horses where the freeway now runs, and they would sell rabbits for sixpence a pair on the corner of Pound and Cranbourne Roads, both of which were gravel in those days.

With the onset of the Depression further schooling was out of the question and in 1933 Keith walked the streets of Melbourne looking for work. He eventually gained a position in a clothing factory. After a few years he resigned to take up a motor mechanic apprenticeship, studying at night at the Working Men’s College (later RMIT). Keith eventually started his own business, leasing premises in South Melbourne from racing car driver Cec. Warren. He serviced the cars in Cec’s “stable”, including a Fraser Nash, a Bugatti (formerly owned by Malcolm Campbell), and the only Invicta in Australia.

Joining the RAAF

Keith had joined the Army Reserve and was soon called up when war broke out in September, 1939. However he decided that he would prefer the Air Force but discovered that, as he was not 21, parental permission was required. This was refused so Keith had to bide his time until 21 (February 1940) when he again visited the Air Force recruiting post. The officer-in-charge greeted him warmly with the reassuring words: “I’ve seen you before; you’re in a hurry to die, aren’t you?”

There was another delay when he was informed during the medical examination that his tonsils were superfluous to requirements. Fortunately the doctor was an acquaintance (Keith had serviced his car) and he was able to expedite matters: the tonsils were removed at a small maternity hospital in Middle Park and a bed was installed in the Matron’s office for Keith’s recovery.

After completing his initial training course at Bradfield Park in NSW, where it was decided that Keith’s eyesight was not good enough for him to be a pilot, he was informed that his lot was to be a wireless operator/rear gunner. Next it was off to Canada and a six month wireless course in an agricultural college at a place called Guelph. Doing Morse Code for eight hours a day was too much for some, and they fell by the wayside. The downside of Guelph was that the Canadians had chosen the same location to establish their cooking school; according to Keith some of their earlier attempts were not the best.

From Guelph the group was sent to Mossbank in Saskatchewan to do a gunnery course. Keith was topping the class, prompting the instructor to pull him aside and warn him: “You are doing too well in gunnery and if you are not careful you won’t be a wireless operator. Instead you’ll be stuck in the rear-end turret, so you had better miss a few targets from now on.”

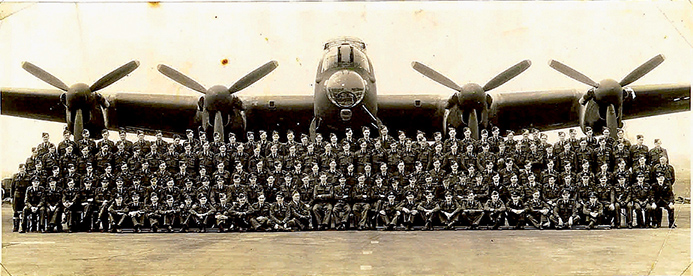

Bomber Command

Once in England Keith soon formed part of an air crew which was selected pretty much at random by the pilot (Paul Hawkins). Shortly after they had commenced training flights Air Marshall Harris took over Bomber Command and decided on the first 1000 bomber raid to take place over Cologne on 30/31 May, 1942. To make up the numbers it would be necessary to use Operational Training Units, including the one to which Keith belonged. Briefings in those days were not particularly sophisticated: “This is the nearest way to the target and this is the best way to get home.” Later briefings were much different; they were more organized and included the use of pathfinders.

Soon after the Cologne operation there was a similar raid over Essen. Keith’s account tells how easy it was to get into trouble:

“We were coming out of the target and were supposed to be heading home. I looked out of the plane and saw the Pole Star and thought , that’s funny, it’s on the port side. We are going the wrong way! I said to the Navigator Mac, ‘Why the hell have we got the Pole Star on the port side-we are going the wrong way.’He said not to be silly, it would be on the starboard side. I said, ‘Mac it’s on the port side, you’d better look at the astrodome.’ Mac took a look and said: ‘Good God, it is too!’ So he asked Paul what course he was following and he said, ‘Oh, blimey, I’ve put the compass on the wrong way round!’ So he turned the compass around. I think if we had kept going we would have ended up in Russia! We got home with just enough fuel to land.” (from “Flak…Fighters and Fliers”, Page 21).

Although these first two ops were in Wellingtons, the crew was then posted to 57 Squadron at Scampton which was being supplied with the newly-developed Lancasters. The squadron did quite a few raids on the Ruhr, Berlin, and various other targets, and half way through his first tour Keith was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Medal. Soon afterwards he was given a commission and became a Flight Lieutenant.

During this time 617 Squadron was formed at Scampton and, because of his expertise in signals, the leader of the new squadron, Guy Gibson, borrowed Keith for many of their training missions. These were highly dangerous (sixty feet above the ground at night) but were a necessary preparation for the squadron’s famous “Dam Busters” raid.

Adventures Aplenty

On the Ground #1 “An amazing thing happened at Scampton…We were all on parade this morning when all of a sudden there was this flash over the other side of the aerodrome and over the tannoy system came an announcement that a photo flash had dropped out of a bomber. The night before we had all the bombers lined up to go to Berlin and fog closed in so much that they had to cancel the raid, so all the aircraft were lined up one after another, all the Lancasters, about 14 or 15 of them…Of course the photo flash set fire to the aircraft, which had a 4,000 pounder on, so you can imagine they were screaming for volunteers.

Paul and I hopped on the side of a fire truck to see what we could do…Paul climbed into this Lancaster and started it up so that it wouldn’t get blown up. A 4,000 pounder blew up – the blast was incredible – but we got our aircraft down into a paddock and the thing bogged! Anyway we saved the aircraft.

We raced back to get another one and we put that in a different spot-it was so foggy you didn’t know where you were going – and that one got bogged as well! Then another aircraft blew up – I think we lost four aircraft with these 4,000 pounders exploding.

As the fog cleared in the day we were all lined up – aircrew, ground crew and all – walking up the aerodrome picking all the broken bits of aircraft….We couldn’t leave it there, of course, as it would have ripped tyres up on take off or landings.

The planes that Paul and I had got out were bogged to their axles with the weight of the 4,000 pounders. The next task was to get shovels and dig them out.” –Ibid, Pages 27-29.

On the Ground #2: “When we were at East Kirkby, part of the bomb dump went up…a lot of these bombs had left hand threads for when they put the fuses in the nose, and they thought that someone crossed the thread and went to turn it back. Well, if you turned it back it blew up. It killed eight or nine of the armourers. Luckily, it was on the edge of the bomb dump and didn’t get right into it.

After that there was another one at Spilsby, which was a satellite aerodrome to East Kirkby. One night the crews were about to take off and there was an enormous explosion and the whole bomb dump went up…aircraft were stopped flying for about five minutes and, when they eventually took off, they had to make up time to get to the target at the right time.”–Ibid, Pages 75-76.

And in the Air #1 (over Essen): “Most of our raids were called collectively ‘The Battle of the Ruhr.’ We bombed Essen, which was the most heavily defended target in Germany, and the most difficult to hit was the Krupp works. We had some bad nights. On 13 January, 1943 we were the only squadron plane to get to the target and, boy, if you got one plane over Essen, then watch out! How we ever got out I will never know – we were badly shot up. Anyway we got home, but we crash–landed and the plane was written off.”–Ibid, Pages 36-37.

In the Air Again #2 (over Berlin): “One night over Berlin we got lost on the way back. We got a wrong wind direction. Mac had done our course and we ended up over the top of a place called Osnabruck. We were caught in the searchlights and hit by flak at 18,000 feet. The aircraft started diving and we couldn’t stop it. Paul yelled for me to come and help him pull the stick back, but we weren’t succeeding much at all…Paul shouted to the Flight Engineer, ‘Cut the motors. Cut the motors.’ He cut the four motors, the stick gradually came back, and we pulled out. The bomb aimer swore blind that we were below the level of a couple of church spires! When we opened the four motors, the rear gunner said he had never seen so much smoke and flame come out. Two of them started well and the other two spluttered and eventually got going. Then we found that we couldn’t stop the blasted plane from climbing, so we got it to a level where we could hold it for some time. Then Paul cut the motors and we drifted down; the motors were then activated and we would fly up again. This is the way we got home.

When we got over the coast and were able to communicate they told us to bail out and send the aircraft into the sea. Mac refused to bail out saying ‘Steve’s parachute has been hit by flak. I’m not going to bail out and leave him behind.’ So we were then instructed to bail out the rest of the crew and the pilot and wireless operator could try and land it. The rest of the crew said they were not bailing out either. They were all jammed behind the main spar and in a crash landing had a fair chance of not getting knocked about…

We got to the end of the runway and Paul said ‘Righto Steve, leave the wireless and come and help me.’ So I went up and as we were coming in to land he said ‘Cut the throttles back’ and we just crash–landed ‘bang’ on the runway. The aircraft broke in half in the middle and you have never seen a greater bunch of rabbits come out of an aircraft. We came out of any holes we could find and there were plenty of them.

We saw part of the tail plane behind us with the rear gunner in the turret, so we went back to get him out. When he got out he said ‘Hawkins, that’s the worst bloody landing you have ever done.’ He turned around, saw the rest of the plane further up the runway and fainted! He came good and we went and did our de-briefing. That was a rough one!”–Ibid, Pages 42-44.

…and Again #3 (Saving Mac): “I used to go off the intercom as it annoyed me talking when I was trying to listen to the wireless. If I was needed, other crew members could press a button and a red light would come on. This night, returning from Nuremberg, the red light came on and I said ‘Yes Paul’. He said ‘Have a look at Mac. He’s gone nuts.’ I looked around and thought ‘What the devil is the matter with him?’ Then I realized he was short of oxygen.

I unhooked my oxygen and hooked it onto Mac, got him on the bed behind the main spar and put the straps around him so that he couldn’t get up. I grabbed his portable oxygen bottle and took a few deep breaths which made me feel better. Oxygen depletion is like being intoxicated-you think you can do things and you can’t. Later on, when we got back, the doctor told me that Mac was within 15 seconds of dying. I had just got him in time.

The next problem was to navigate the aircraft back. Mac’s workings were confused so I gave Paul the best course I could from what we had. On landing they raced Mac off to hospital. He came good after a night in bed and his oxygen level had returned to normal.”–Ibid, Pages 44-45.

The White Feather

Keith’s bibliography contains a brief record of all 62 ops in which he participated before he was shot down. Very few were uneventful: there were a number of occasions when fuel ran low, and there were a number of crash landings. Operation 33 (20 June 1943) was a long flight which necessitated a landing at Maison–Blanche in French North Africa. The next operation (23 June) was Spezia (Italy): “…bombed battleships in harbour–port inner and starboard outer knocked out by flak over target – could not climb over Alps on way back to base in UK on two engines so we set course back to Maison–Blanche and, lo and behold, the idiots fired at us and hit us as we came in to land.”–Ibid, Page 280. The next operation (#35 on 28 June) was also eventful as the pilot passed out at the controls. It was after this op that the Wing Commander, noticing that Keith’s crew was the only one to complete 30 operations, decided to call an end to their tour. Keith was promoted to Flight Lieutenant and ordered not to fly for six months.

It was during 1943, towards the end of his first tour, that Keith received an anonymous letter from Australia. It contained a white feather and a letter which “…said that I had left Australia in its hour of greatest need, was living in luxury in hotels in London, going on leave all over England, and thoroughly enjoying myself at the Government’s expense. Australia was in dire straits – the Pacific war had started of course – and that I had left it. It finished up saying something like , this is the coward’s way of getting out of fighting for your own country.”–Ibid, Page 71. While Keith laughed the matter off, his Wing Commander took a dim view of the affair.

Although he had been stood down for six months, Keith’s second tour started early (14 July 1943) when he started flying with different crews out of East Kirkby. Operation 42 over Munich on 14 October was again eventful: “…chased by two fighters – rear turret badly hit – pilot asked me to check rear gunner – I said we have to fly below 10,000 feet as the oxygen tube was broken, also intercom – dived to 9,000 feet – I then climbed into turret – what a mess – cold as I only had battle dress. Near UK coast Flight Engineer came down for me to return to wireless set – called up base and told them of our problems – they said to come on a priority landing.”– Ibid, Page 282.

After operation 46 (Berlin on 22 November, 1943) Keith was again grounded for a rest from operations; this time on the orders of Air Marshall Harris and Air Vice Marshall Cochrane. However by 16 January, 1944 he was back in the air. Operation 49 was difficult as the Bomb Aimer was killed and Keith had to fill this role. Not being familiar with the task he had to ask the pilot to go around again: “…language on intercom very colourful.”

Operation 61 was on D-Day (6 June, 1944) over the coast of Normandy: “Bombing gun emplacements above Sword Beach landings – great sight seeing Channel covered in invasion craft.”

Off to the Palace

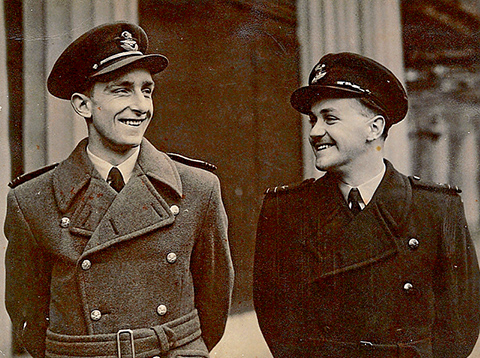

Although Keith had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal half way through his first tour of duty, it was some twelve months later that he received his invitation to Buckingham Palace for the official presentation.

Keith was allowed to take two friends: Anita (his fiancée) came down from Glasgow and Mrs. Anderson, a family friend, was also invited. The night before the presentation Keith and Anita stayed with Mrs. Anderson and there was a bombing raid: “…they practically blew the street out (but) luckily we didn’t get hit….The next day we…got the Tube to London, walked out to a taxi, and I was about to say ‘Take us to the Palace’ when the driver said ‘Oh. You’re going to the Palace are you, mate?’ I replied ‘I could shoot you. I have been looking forward all week to getting into a taxi and saying ‘Take us to the Palace.’ He replied ‘Oh. Every officer I see dressed up with two ladies today, I know they’re going there. I’ve taken so many already.’”–Ibid, Page 90.

When a recipient was called forward they played the National Anthem; for Keith it was Waltzing Matilda! Keith had actually met the King previously when he, Churchill, and other leaders had visited Scampton immediately after the Dam Busters raid. As he pinned the decoration on Keith’s tunic the King said “I’ve met you before at Scampton, Stevens.” Keith however had observed the Lord Chamberlain whisper something to the King just before he stepped forward, so the King’s memory was not that good!

Shot Down

Keith’s record of Operation 62 on the night of 7/8 July, 1944 reads as follows: “St. Leu D’Esserent caves storage site for V1 and V2 rockets-hit by flak on the way in – after bombing attacked by two fighters – A/C on fire, also holes in body of A/C – we decided to abandon A/C. Bailed out at 18,000 feet – lack of oxygen a big problem – hit tail plane with head and shoulder – A/C being shot down all round – enemy shooting down parachutes but missed me – landed on enemy territory – rather hard.”–Ibid, Page 286. (The raid had in fact been a success and probably saved London from attacks by a further 4,000 rockets.)

After travelling at night to elude the Germans, Keith was eventually captured and taken for interrogation by a Gestapo officer. “Then he did the unforgivable thing, which you never do to the enemy…he turned his back on me…I dived into the back of him, hand over his mouth, knee in the back of his neck, and pulled his head back with both hands. Whether I broke his neck I’m not sure, but in my sleeve I had a hacksaw blade which was sharpened on one end like a razor, and that came in very useful. I left him on the floor and dived out the window…I wondered how the devil I was going to get out of all this.”–Ibid, Page 115.

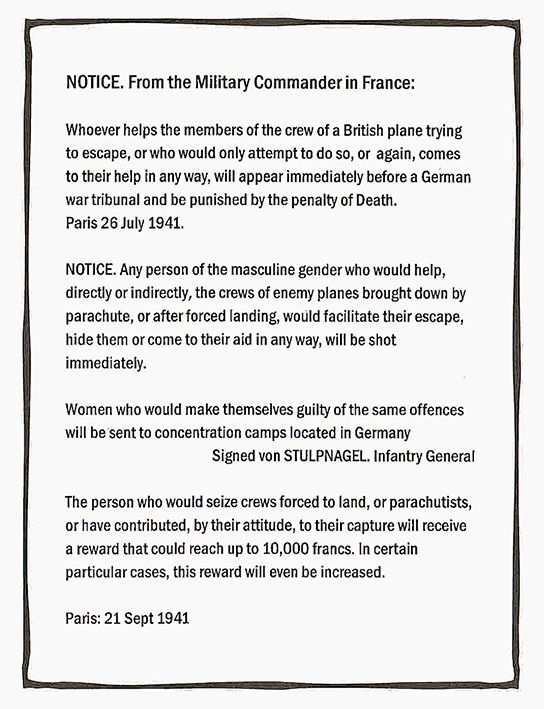

Keith spent several more days on the run before taking his chance with a couple of peasants who came along in a dray. They took him to their farmhouse and when it was dark a solidly built Frenchman named Georges Morel paid a visit. His intention was to cut Keith’s throat but, after some quick talking by Keith, he left only to return with Madam Violet, the leader of the French Resistance in that northern part of France.

For the next three months Keith was hidden by members of the Resistance and even participated in some of their ventures. On one occasion he went with a group to blow up a railway bridge but the mission was not successful. Next day a Frenchman rushed into the estaminet (or bar) where Keith was hiding and kissed him on both cheeks, several times. When he calmed down Keith learned the reason for his excitement: a troop train had been crossing the bridge which had then collapsed under the weight. On another occasion one of his companions handed him a piece of piano wire with a small wooden handle at each end. When Keith enquired as to its use it was explained that, if he approached a German from behind and used it appropriately, the little device could swiftly separate the German’s head from his shoulders.

Usually accompanied by a young female member of the Resistance, Keith slowly made his way west by push bike. “They were extremely brave people, risking their lives to save mine.” (In fact research by British Intelligence Service MI9 found that over 30,000 lost their lives in helping to get just 3,000 to safety.)

On 2 September, 1944 Keith was taken from Giencourt, one of eight safe houses in which he sheltered, up into the main street of Clermont when an American tank appeared. An officer called out “Does any goddam idiot here speak English?” When Keith responded the American, rather taken aback, said “God Almighty! Not an Aussie. What the hell are you doing here?” After dispensing some rough justice to collaborators, the celebrations began.

Next day Keith started for the coast: initially by bike, then by jeep, by DC3 to Amiens, and finally by jeep through Caen to the coast. The English Channel was then crossed in an empty tank–landing craft after which Keith was taken to London for interrogation by MI9. After signing a document regarding non–disclosure of information about his escape, Keith was cleared to go back on operations. Back at base, however, although keen to get back in the air, Keith was informed that MI9 had instructed that he was not to fly in Europe over enemy territory: he knew too much and the Gestapo would not let him slip through their fingers a second time. Instead he was posted to Pithelly to train all the Signals Leaders of Bomber Command. This was Keith’s final posting prior to his repatriation to Australia early in 1945.

Time for Romance

Keith’s initial crew included a Scot (Mac) who was the navigator. Not long into the first tour Keith saved Mac’s life when his oxygen failed. So, on the next leave, he invited Keith to stay with him and his family in Cardonald in Glasgow. Mac’s mother, Mrs. McKenzie, had tearooms near Glasgow University where an Anita Grieve happened to be a student. Anita was invited to make up a foursome and a romance soon developed. Anita and Keith became engaged in 1944 and plans were in place for a wedding on 2 September. Then the war intervened: Keith was shot down on the night of 7/8 July and Anita and his parents were informed that he was “missing, believed killed.” Coincidentally it was on 2 September that Keith made contact with the Americans in France.

From the offices of MI9 in London Keith was able to make a surreptitious phone call to Anita. Wedding plans were resurrected and the wedding took place in Glasgow on 4 October, 1944. After a 12 hour trip to London the couple eventually found accommodation at the Grosvenor Hotel. They had only just booked in when the air–raid sirens sounded with the result that Anita and Keith spent their wedding night sheltering in the basement! After ten days Keith reported to Brighton from where Australians were being repatriated. It was another eight months before Keith and Anita were re–united in Australia.

After his discharge in May, 1945 Keith eventually returned to the motor trade and later became the director of a sports car firm. He became involved in Legacy, was on the Board of Management of the Victorian Automobile Chamber of Commerce, and became a councillor in his local municipality. He also helped to establish the Australian branch of the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society and was president for a number of years.

On retirement Keith and Anita moved to the Village Glen in Rosebud in 1988. It wasn’t long before Keith became President of the Residents Club and he was one of the instigators of the Village Anzac Day ceremony. He and Anita took active roles in Family Day and other activities.

In 1983 and 1990 the couple made sentimental journeys back to France where Keith was able to renew his friendships with a number of members of the Resistance movement.

After almost 70 years of marriage, Anita died in 2013, aged 93.

Keith’s Philosophy

“Someone asked me once why I didn’t really get too upset when things sometimes got difficult in business and throughout life. My answer was simple. I always look back to the time when I was shot down and was sitting under a tree in a foreign country – an enemy occupied country – and I didn’t know the language, and I had nothing to eat. I look back at that and think nothing could get as bad as that. Life could never get as bad as that, so its the only way to have a happy life.”– Ibid, Page 256.

Footnote: A few months ago several World War 2 veterans were presented with the Legion of Honour at the French consulate in St. Kilda Road. Keith Stevens was to be a member of this group but unfortunately suffered a fall in the week prior to the ceremony necessitating a stay in the Alfred Hospital. Keith is now a resident of Ti Tree Aged Care Facility in Rosebud and on Thursday 16 April the Honorary Consul-General of France in Melbourne made a special visit to the Facility to present Keith with the award.