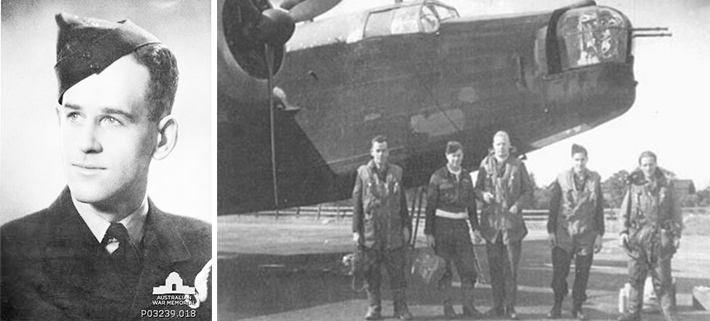

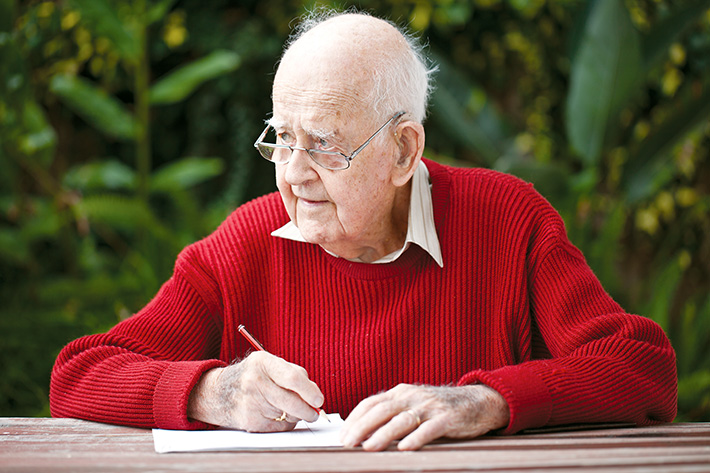

Don Charlwood was an RAAF navigator in Bomber Command during the Second World War. In two autobiographical books, No Moon Tonight and Journeys into Night, Charlwood recalls the excitement, tedium and terror of navigating nighttime air raids in Europe and his years in Bomber Command. He is also the author of All the Green Year, a novel about boyhood and adolescence in a coastal Australian town (Charlwood grew up in Frankston), and Marching as to War, a memoir of life in Australia between the two world wars. Here he remembers the tragedy and utter futility of war; a time without a future.

OUR generation and our parents’ generation were always conscious of two monstrous markers in their lives to which everything else was related. There was “before the war” and “after the war”.

Our parents first used these terms; they were mostly born between the late 1870s and the early 1900s. They might say, “Tom was born before the war”, or “Julia was married the year after the war”. That was their war, the Great War of 1914-18, “the war to end all wars”.

We, their children, learnt in our school days that the Allied sacrifices of that war had made our world “safe for democracy” and we were taught to revere the Anzacs for their part in it. But from the vengeance of the 1919 peace terms, Nazism resulted and the unthinkable came – our war.

The name Great War all but vanished; instead we now had a First World War and a Second World War. Ever after our generation has looked back on youth “before the war”, before 1939 when the great economic Depression merged into our war. Now, in the 21st century, as our generation vanishes, so too are these monstrous markers vanishing.

During our war, the men I knew in Bomber Command, avoided using the term “after the war”. It suggested expectations and would have been thought of as tempting providence. The poet Marya Mannes wrote a sonnet Love in War that might well have been for us. It began:

We are masters of the present tense,/Having imposed upon ourselves a law/Prohibiting the future.

There was even belief among some of the Bomber Command leaders that hope was the enemy of good morale, that it sapped courage, that we should not think beyond the bombing raid that night. Yet I remember unmistakable signs of hope among ordinary aircrew. I became aware of them in September 1942 when our crew of Australian and RAF sergeants arrived at the Royal Air Force station Elsham Wolds, in Lincolnshire, UK.

Our posting was to the four-engine Lancasters of 103 Squadron. For the pilot and navigator this was the culmination of 18 months of training. In six or seven weeks we were to “dice with death”, as aircrew parlance had it.

We were allocated beds in long barracks, which were camouflaged on the outside. Most of the aircrew sergeants were out for an operational briefing and their grey blankets were folded around their pillows in the regulation way. The barracks were cold, the pot-bellied stoves long out. Beside each bed was a low chest of drawers. On most of these were photographs, each one of a girl, the girl with whom an unknown man shared secrets and confided hopes for a future together after the war. Most of the photographs had been taken in studios and had been back-lit in the manner of the day. The girls’ hair styles resembled those of contemporary film stars, their eyes gazed longingly, their lips slightly apart. Most were of girls from the British Isles since most aircrew were from the RAF. The photographs contrasted with everything else in the barracks; the bare floor boards, the metal beds with their folded blankets, the ash spilt from the dead stoves.

We already knew, of course, that RAF men could see their girls whenever they went on leave. In our training days we had envied them, but we realised now that this wasn’t as good as it seemed: to say good bye to a girl in the early hours of the morning with the likelihood of flying over Germany that night had a terrible unreality to it, a possible but unutterable finality.

On the evening of our first day the absent men came tramping back into the barracks, their manner subdued. They had not long been briefed to fly to a target somewhere in Germany. There was little opportunity to do more than exchange a few names. Predominantly they were RAF, but there were Canadians and Australians and a couple of New Zealanders among them.

With their arrival the barracks looked like the senior dormitory of a third-rate boarding school. Some of the men, in fact, had actually come from school straight into the air force. The average age was between 22 and 23. Some of us pulled up the average: I had just turned 27, Geoff Maddern, my skipper, was 26.

Regardless of age, we looked on these men with respect; they were already operational. Some had done 10 or 12 of the 30 operations over Germany and Italy required of us. This was called a “tour”. We glanced at the operational men as if their demeanour might tell us something of ourselves in another few weeks. They were restrained, monosyllabic, preoccupied. We wished them luck as they left. Well after dark, as we were settling to sleep, we heard their planes roar overhead. I drew my blankets closer.

In the early hours of the morning we were aware of the operational men coming back into the barracks, aware too that there weren’t as many of them as had left the night before. I had feelings of unreality; we had seen no battle, no stricken planes, the loss had taken place while we slept. When we got up the survivors were still sleeping; a few of the beds near them were empty. The girls smiling from the photographs next to these beds had no one to cast them their usual affectionate glance.

Before we left for breakfast, three men from the euphemistically-named Committee of Adjustment came in and emptied the contents of a chest of drawers into each missing man’s kit bag. There too went the photograph of the girl, of his hopes for life together after the war. The bedclothes were taken, the bare metal bed left for a newcomer. Somewhere, girls were waking to this day, not knowing.

Within a couple of weeks most of the operational men in the barracks vanished, their girls’ photographs vanishing with them. Though the squadron was haemorrhaging, numbers never changed, only faces; transfusions flowed from Training Command – eager youngsters most of them, caps aslant, faces shining, spirits assured. We who were older could see that for most of us there wasn’t going to be an “after the war”. Most replacements were RAF men, but others came from the dominions and allied countries. The supply seemed endless – the best of men, carefully selected, thoroughly trained, most bringing photographs to replace those gone.

My initial impulse had been to cry out against such wholesale loss of first-class youth, but again and again the realisation returned to me: the Nazis were occupying most of continental Europe, only Bomber Command could strike them. All over Britain were servicemen from the occupied countries; the struggle was as much for their homelands as for Britain. Everything depended on Bomber Command maintaining its resolve.

We were in the barracks seven weeks and now had our own Lancaster. Geoff said, “This place is no good for morale, I’ll see if I can get rooms”. In this he succeeded. Each had its own pot-bellied stove. In the one Geoff and I shared I dared put out the photo of Nell East, the Canadian girl I hoped to marry. It was in a leather folder, my family members on its other side. On operations I used to shove it down my battle dress as a talisman. Each of us had our superstitions but in one we were united: we all wanted the same WAAF driver, 18-year-old Peggy Forster, to drive us to and from our plane. This she did, even returning once or twice from leave.

We had three married RAF men in the crew and Geoff was much concerned for them, particularly for Arthur Browett, our rear gunner, whose wife was in an advanced state of pregnancy and suffering an acute state of anxiety. Geoff and I passed her delicacies from our hampers from home. There came an evening when Arthur failed to show up for briefing and we had to take a replacement rear gunner. Next day he was paraded before the Wing Commander. I think all he could plead was that his wife was prostrate with anxiety. His failure to fly never occurred again. When his wife’s time came their baby only lived an hour. They never had another. Of all our RAF men none had children, even when the war was over. Only Geoff and I had families when our operational days were behind us. I tell these things conscious that it was not only men who suffered in the Bomber Command war.

In the room Geoff and I transferred to we no longer saw empty beds. We slept soundly; nightmares belonged to the waking world. In the morning as I drew our black-out curtains I would think, “How have we fallen into this grotesque existence?” Gradually I learnt to shrug it off and settle to the day’s routine. It might have steeled our resolve had we been told what barbarous acts the Nazis were perpetrating, told particularly of the extermination camps. But I doubt that we would have believed such reports. We were a cynical generation; we had been alerted to war propaganda in our school days, when we had learnt of the false accusations made against Germany in the Great War. How could we believe now that millions of our fellow beings were being “put down” with industrialised precision?

As 1943 began we had completed only six of our 30 operations and had seen no crew reach the end of a tour. Four senior crews were taken off operations early because Training Command was running out of pilots with four-engine experience. Other crews reached more than 20 operations and were then lost. One was lost on its 29th operation. Then, on 8 April 1943 – the target was Duisberg – we reached 30, the first on the squadron to survive in eight months.

I see myself writing in the navigator’s log: “0245 landed Base”. It is scarcely to be believed – our lives have been given back to us! It is a re-birth! We free ourselves from the umbilical cord of oxygen and intercom, pass down the long belly to the steps, emerge into the fresh Lincolnshire night, septuplets from the womb of our Lancaster. Peggy, our driver, our midwife, embraces us. She drives us then to the operations room for the usual interrogation by intelligence, but the group captain and our much-loved squadron medical officer intervene to congratulate us. Incoming crews are cheering. Thirty ops at Elsham Wolds is possible after all!

Geoff was the first to realise the loss about to fall on us: loss of our crew. After almost nine months of flying together, in training and on operations, we had become a devoted, disciplined team, utterly dependent on each other. It was Geoff who had fashioned us, who wished us to be an all-NCO [non-commissioned officer] crew, undivided by commissioning. Though we had striven to do what the RAF demanded of us, we had each faced the unspoken probability that we were together “till death us did part”.

Geoff and I cabled our parents; I also cabled Nell East in Canada. After we had slept we took our overjoyed ground crew for a night out at the Crosby in Scunthorpe.

That night was the last time all seven of our crew were together. In 1944 Nell and I married.

Four of our crew were to live to their 90s, three until last year. Of our crew of seven, six have gone on their Last Op. I fancy they are impatient.

This essay by Don Charlwood was first published in the Anzac Day edition of the Frankston Times in April 2012.

2 Comments

Knowing Don Charlewood A.M.in his twilight years was a real honour for me. He wrote many books on the subject of shipwrecks along the Victorian coastline. One of those famous ships, the Schomberg which ran aground on a reef near present day Peterborough carried his grandmother and great grandmother . His interest in those forebears lured him from his bayside home to Cape Otway in Victoria to investigate and write some of the best books still available today on the subject. VIsit burgewoodbooks.com.au for further information.

Just came across your lovely comment Len. Thank you. Doreen